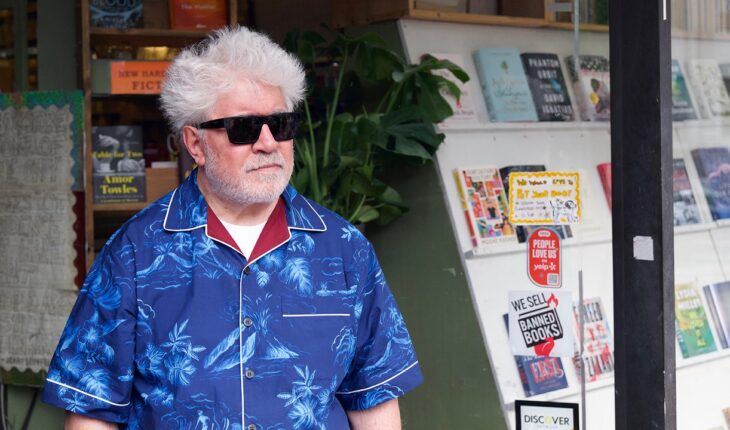

When Pedro Almodóvar asks me what I thought of his latest feature film, The Room Next Door, I decide to be candidly honest. I tell him the truth, which is that I started crying after I left the press screening. “It’s good to cry over a movie. The tears bring relief and they aren’t like the ones caused by pain in real life,” he says, with the authority of someone who has shed both types of tears. Outgoing and talkative, he appears to be in an excellent mood. And yet, just minutes earlier, he was an image of despondency.

I found him in his office at El Deseo, his production company, staring at his glass of tea with a saccharine tablet. He looked like someone contemplating a disappointing failure. I was reminded of a scene at the beginning of his 1995 film The Flower of My Secret when the weight of all the misfortunes faced by the character played by Marisa Paredes converge on one moment. Unable to remove her too-tight boots, she is plunged into despair. As I waited in the doorway, a small crisis seemed to be unfolding, and neither the press liaison nor the production company employees knew how to resolve it. I feared that this interview might not go so well. “The tea is cold, the saccharine won’t dissolve,” he lamented in a tone that went beyond mere grumbling to an expression of undeniable defeat.

Here, I thought, is someone who has won two Oscars, a best-director prize at the Cannes Film Festival, the Donostia Award for extraordinary contributions to cinema at this year’s San Sebastian Film Festival, and would soon win his first Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival (this interview took place days before he received that honor). And yet at that moment, he appeared completely overcome by a minor inconvenience. Suddenly, however, his mood changed, he looked up, smiled, and invited me to come into the room. Everything was perfect. Did I want anything to drink? Just water, thank you. What did I think of The Room Next Door? One of the best films of his career and the most moving, I said. I found myself crying on my way home after I saw it. From that moment on, the conversation flowed without stopping. And the tea sat there, untouched, on the table.

Vanity Fair: San Sebastian was the first festival to screen one of your films [Pepi, Luci, Bom in 1980] and Venice was the first one outside of Spain to include a film you had made [Dark Habits, in 1983]. Venice was also the first festival where you won an official prize [in 1988 Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown won prizes for best screenplay and best actress for Carmen Maura’s performance]. Going to both festivals this year feels like it’s closing a circle. Is that how you see it?

Pedro Almodóvar: I’ve been to Cannes many times, but the first wasn’t until 1999, with All About My Mother. Venice was the first international festival that truly opened its doors to me, though there were challenges. Part of the selection committee was completely opposed to including Dark Habits, among them Gian Luigi Rondi, the Italian director, who was a Christian Democrat. I ended up in the Mezzogiorno Mezzanotte section, dedicated to films by young people, because Enzo Ungari, a collaborator and friend of Bertolucci, fell in love with the film. They called me a “Mediterranean Fassbinder.” It was a formidable description to live up to. Added to that, the Italian release of the film was given the title L’Indiscreto Fascino del Peccato (The Indiscreet Allure of Sin), inspired by the success of Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire which had been released a few years earlier. The sensationalism of the titles of Italian releases is matched only by that of Spanish films.

The Room Next Door is centered around a former war correspondent [played by Tilda Swinton] who, faced with her imminent death, reaches out to a friend who is a bestselling author [played by Julianne Moore] to keep her company during her final days. It’s now been more than 40 years since you created Matador, a film that was also focused on death and, specifically, its relationship to sex. You made two other films that also addressed similar themes, Talk to Her and Pain and Glory. Do you see a common theme running through all four works?

With Matador I had decided to make a film about death and I wanted to see where the theme led me. In that movie death was linked to sexual pleasure. It was very difficult to talk about it; from a psychiatric point of view, everything around this topic is complicated. Matador was created with a younger perspective. With The Room Next Door, I didn’t want it to be gloomy or hard to watch. I didn’t want to make something that felt like a work by Haneke. However, Martha, Tilda’s character, embodies a debate that is taking place around the world, regarding euthanasia and whether it should be legal. In Spain it is often not freely provided to those who ask for it because conservative lawyers and judges intervene. [In 2021, Spain became the fourth country in Europe to legalize euthanasia.]

It seems to me that the law should correct that. Martha is a completely rational woman in full control of her senses, and she wants to leave this world cleanly and directly. Accompanying her at this time and to help illuminate the way is Ingrid, Julianne’s character, to whom I feel close. She allows herself to make jokes at difficult moments, and she fills everything with life, although behind it all there is this dark tunnel. It was essential to me to avoid the dramatic and the overly sentimental. That’s a danger of stories like this one—sentimentality. I wanted to avoid melodrama, both in order to create a tougher film but also at the same time to shine a different light on the story. That’s why I collaborated with these two actors who have a certain grace. The three of us worked together, sitting around this table where you are now, and also at my home. They understood very well the tone I wanted to give to the film. They’re superb actors.