If the earthy, workmanlike professional ramble of The Bear is to your taste, but you’re looking for something with actually high stakes, Max’s new series The Pitt (premiering January 9) just might do the trick. The series is from R. Scott Gemmill, a longtime writer and producer on the mega-hit hospital drama E.R. Gemmill returns to that fraught environment for The Pitt (with E.R. showrunner John Wells as executive producer), another verite-ish look at the frenzied lifesaving work of emergency room doctors and nurses.

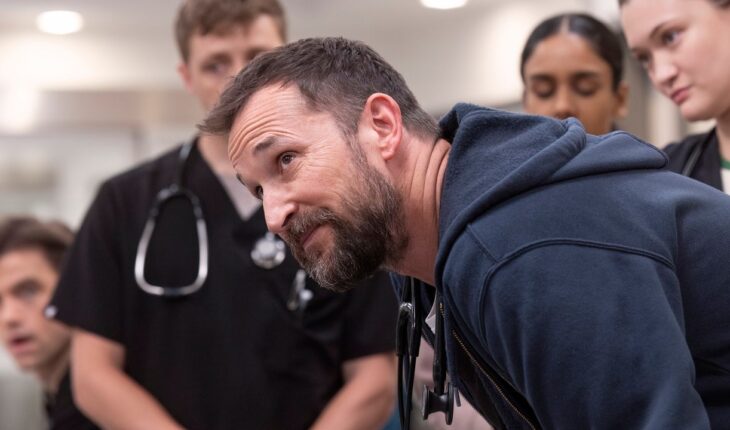

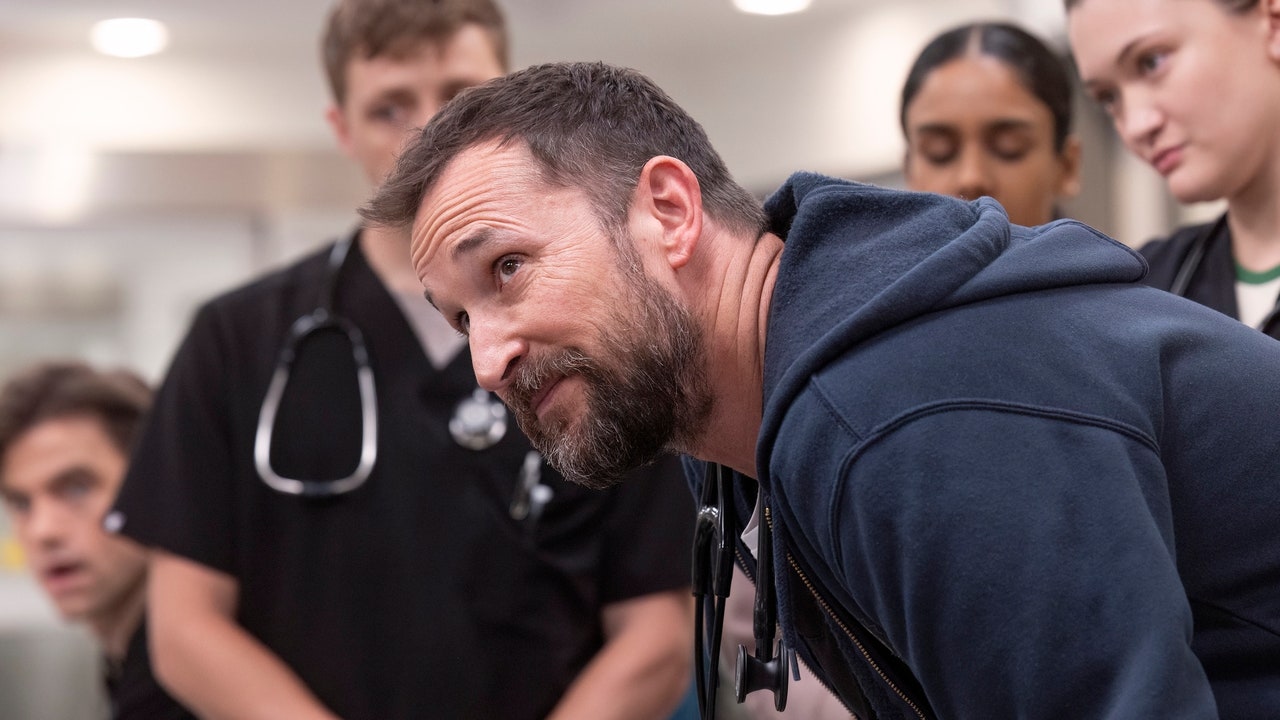

The show is not a continuation of E.R., though the presence of star Noah Wyle, once the cute young upstart but now the world-weary old pro, may confuse that matter some. Wyle plays the attending doctor at a struggling Pittsburgh hospital, prized for its expert care but hammered by budget cuts and under-staffing. Wyle’s Dr. Robby (as he’s called) is frustrated by these circumstances, but still deeply committed to the work. A good thing, given that his hospital is a teaching one, and four new interns have just clocked in for their first shift. These wide-eyed rookies, either recklessly overconfident or overly squeamish, need his steady guidance.

The Pitt’s conceit is that the season covers one 15-hour shift in the E.R., each episode unfolding over one agonizing, nail-biting hour. Which means that there’s not much room for character development—how much can one person grow in less than a day? Gemmill argues that, well, they can change at least a little bit, as we watch the young doctors—King (Taylor Dearden), Santos (Isa Briones), Javad (Shabana Azeez), and Whitaker (Gerran Howell)—learn valuable lessons and reveal backstories amidst the chaos of mortal crisis. Sometimes this is done subtly; other times, The Pitt gets a bit broad and generic in its quick-sketch characterizations.

An all-in-one-day premise also strains the limits of narrative credibility. I’ve no doubt that many wild and awful things come rushing into emergency rooms every day. But The Pitt asks us to believe that the entire spectrum of human suffering, folly, and danger can be encountered in just a matter of hours. In the ten episodes I’ve seen, there is suspicion that a patient is being trafficked; an interconnected series of fentanyl accidents; worry over a potential school shooter in the making; an internal drug investigation; a drowning victim; an explosion victim; a victim of a racially motivated assault at a train station; a conflict over a teenager’s chemical abortion, and more.

It’s all a bit much for less than a single day, a soapy Grey’s-level abundance that clangs awkwardly against the studied realism of the medical speak and the low-key naturalism of the performances, mostly given by non-household-name actors. We are meant to view the show as docudrama, but then some new big plot is wheeled in through the doors and the show swoops up into melodrama. Melodrama is, however, preferable to another of the show’s modes, which is didactic moralizing on a pertinent social topic.

Still: The Pitt is awfully engrossing throughout, a show that strangely but effectively intertwines prestige TV trappings with the more basic tropes of network workplace dramedy. Wyle is an endlessly compelling lead. Many years of playing doctors have trained him well; his bedside tone, personable and clinically distant at once, is a precise depiction of the guarded compassion of a real doctor. Wyle deftly manages the shifts in emotional temperature as each hour unfolds, selling us on the relentless roller coaster of it all.

Wyle’s commanding performance is a key part of the show’s most successful aspect—the manner in which it evokes what it is to encounter healthcare workers in the trenches of their profession. I’ve been lucky enough to not spend much time in hospitals, but when I have been in those dreaded places, I have always been awed by the calm, pragmatic, outwardly dispassionate work of doctors and nurses. The Pitt isn’t an outright veneration of these people; they are fallible, arrogant, demanding, sometimes too callous in the face of terrified patients. But they are doing something remarkable; to call it miraculous would be an insult to all the time, effort, and money it takes to acquire those skills.

The Pitt is at its best when it is soberly capturing the wonder of that everyday care, carrying us on a surveying tour of a liminal world, straddling life and death. It’s also accomplished in making us understand the maddening influence of money on these matters, especially as more and more hospitals are brought under the management of private equity, which wants only to leach out as much money as possible—the well-being of employees (and patients) be damned. The Pitt is a fitting post-COVID tribute to the helpers, and a rattling admonishment of those who would make these vital places that much less prepared for the next round of disaster.