Woe is the music biopic—typically, anyway. The genre is often plodding and expected, a rote sketch of life and career peppered with renderings of songs better enjoyed in their original form. A few directors have tried to shake things up over the years—perhaps most notably Todd Haynes, whose 2007 film I’m Not There is an odd, abstract conjuring of singer-songwriter Bob Dylan’s spirit. That film is peculiar enough that one had to assume a more traditional, more accessible movie about the generation-defining artist would eventually be made. And so, 17 years later, we have A Complete Unknown, a look at Dylan’s early career from James Mangold—director of the programmatic Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line. Ho hum.

Except! A Complete Unknown (opening Christmas Day) is, much to the surprise of this critic, not at all staid and perfunctory. Even a skeptic can be swept away by its heady mix of laidback assessment and genuine awe. The film does loosely follow a plot: a young Dylan arrives in New York from Minnesota and falls under the aegis of Pete Seeger (Edward Norton, prim and sweet) on his way to forging a path out of folk and into the revolutionary mainstream. But it is mostly a music movie, featuring scene after scene of Dylan performing at various venues while people (including us in the audience) look on in wonder. A Complete Unknown doesn’t tell us much new about an oft studied icon, but it does, like I’m Still Here, persuasively capture his essence (albeit in a very different way).

Dylan is played by Timothée Chalamet, the young movie star of the moment, in a shrewd bit of casting. Chalamet has the rangy, boyish appeal so central to Dylan’s nascent image, but ably complicates the picture with flecks of haughty arrogance, mercurial temper, aloof disregard for the feelings of those around him. While we’ve seen that kind of portrait of an artist before—surely most of the greats have at least a dash of cruel vanity in them—Chalamet makes it fresh. To watch him is to feel what so many other characters in the film do: an affection and a curious sense of loss as he drifts away into the lonely mists of talent and fame.

Chalamet’s Dylan returns to us, close and blazing, in the singing scenes. The actor and Mangold spent years honing the performance, which is half mimicry, half reinterpretation. Their results are beguiling. Classic songs like “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” and “Like a Rolling Stone” (and many more) are both nostalgically remembered and discovered anew in the film, a magic trick that keenly approximates what it might have been to first see Dylan strumming away in some downtown club and be staggered by his prodigious acumen.

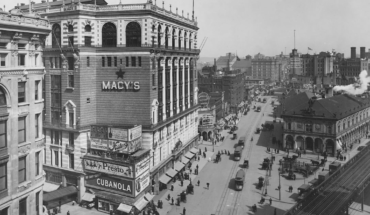

Which may all sound grandiose. But A Complete Unknown is a disarmingly humble film, mellow in mood and cadence. It ambles through the early-mid 1960s, in a vividly rendered period New York City. (With occasional stops in Newport, of course.) There are no druggy, histrionic fits; all hotel rooms remain un-trashed. The only flares of discord are in Dylan’s slightly troubled romantic entanglements, with a character based on a real ex-girlfriend and played by Dakota Fanning, and Joan Baez, played (in beautiful singing voice) by Monica Barbaro. But even those rows are relatively mild, women huffing with hurt and resignation as they, like Pete Seeger and so many others, let Dylan wander off into his solitary greatness.

Is the film giving Dylan a pass? That’s a question for the true fans, who know much more about the intricacies of his personal life than us laypeople. But the film’s perspective—rapt if glancing—probably won’t stir much rancor either way. That could be to the film’s detriment. In one argument scene, Fanning’s Sylvie angrily complains to Dylan that she knows nothing about him; he’s always at a mysterious distance. She’s not wrong. The Dylan of A Complete Unknown is almost exactly that: an enigma enshrouded in the enduring cultural majesty of his songs. It’s either a narrative failing or clever, deliberate metatextual obfuscation.

When Chalamet is up there singing, though, it doesn’t much matter either way. One is transported out of doubt in the simplest of ways, by good songs staged with swooning, justified reverence. The movie’s chief success is in convincing us of the director’s fascination, of the fascination of generations of fans, of the fascination of even the Nobel committee. Maybe Bob Dylan really was the earthquake he’s long been purported to be. At least he is in this compelling vision of the dizzy blooming of genius.