Mary McFadden, “High Priestess of Fashion,” Onetime Vogue Editor, and CFDA President, Has Died

By Laird Borrelli-Persson – September 14, 2024

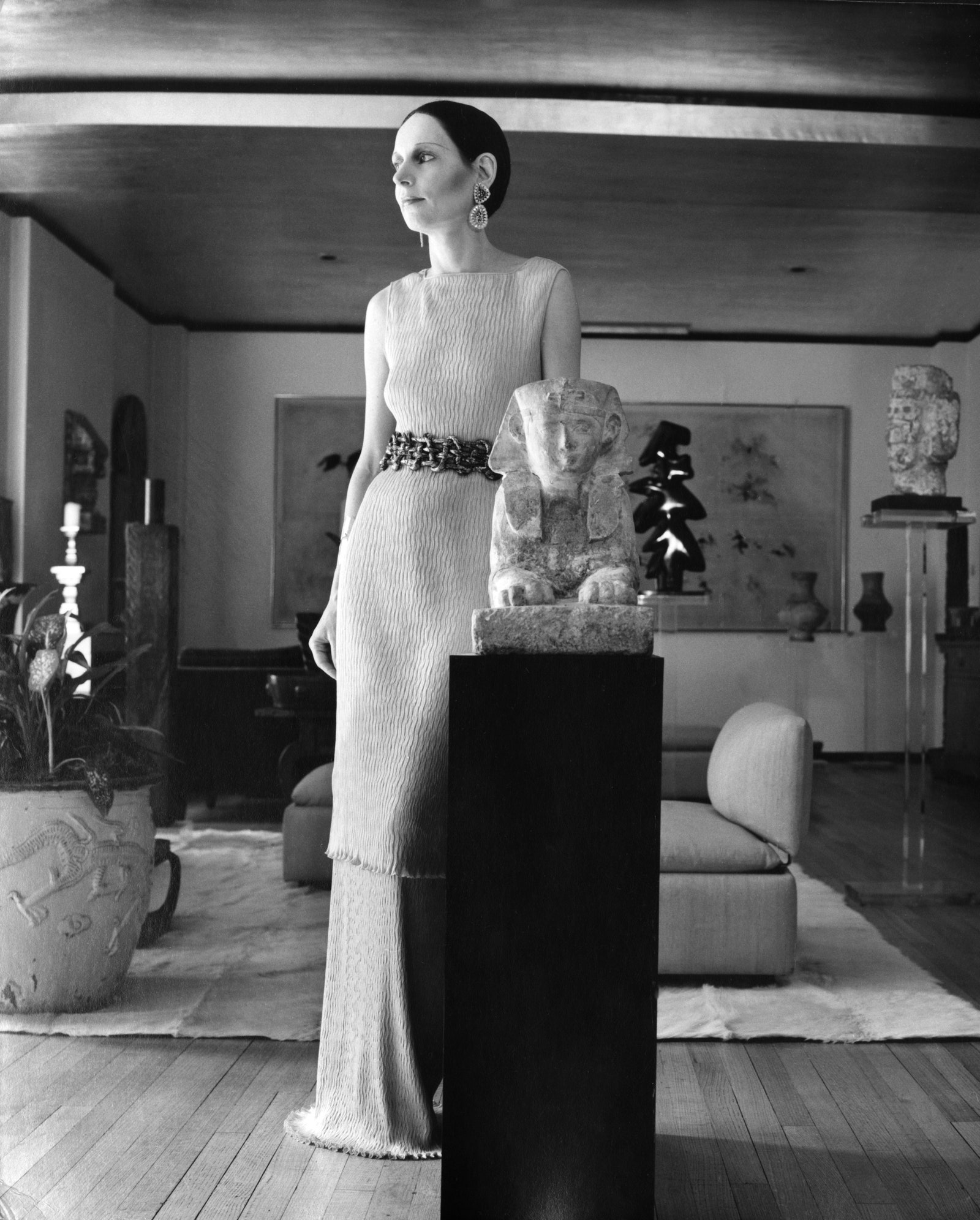

Fashion designer Mary McFadden wearing a sleeveless gown with Fortuny-style pleating, belted at the waist.

Photographed by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, circa 1980

Mary McFadden died Friday on Long Island. She was 85. High Priestess of Fashion is the title of a 2023 catalog she coauthored to accompany a monographic exhibition of her work at the Allentown Museum, and it is rather an evocative turn of phrase, as it conjures ancient worlds, which the designer consistently mined for inspiration, and her own austere and regal appearance. There was always a lot going on below the surface, in her personal and professional life. McFadden was a member of the jet set and a noted entertainer and collector, as well as a Vogue editor and onetime president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. A romantic, McFadden was married a number of times. Justine Harari, her daughter from her first union, died in June 2023.

Earlier this year, McFadden’s work (which is much coveted by a number of Vogueeditors) was on show at Drexel University. The Philadelphia retrospective, “Modern Ritual: The Art of Mary McFadden,” justified a dive into the archive. It’s fair to say that McFadden has long been a Vogue favorite. Her first wedding was featured in its pages in 1964, and the transplanted New Yorker did merchandising for the magazine when she moved to South Africa later that year. Back in Manhattan in 1970, McFadden became a special projects editor at Vogue. It was the clothes that she had designed for herself while living in Africa—and then wore to the office—that became the jumping-off point for her brand. “Diana Vreeland helped me enormously. She was very warm and helpful—a best friend,” said the indefatigable designer.

McFadden was a world-builder before the marketing term existed; she also built a brand around herself. It’s not just that her clothes reflected her own styles and interests; they were an extension of how she existed in the world. Yes, she wore her own clothes well, but it went deeper than that. “I pick up bits and pieces wherever I travel,” she said when speaking to Vogue about her approach to collecting and interior design. “The idea was to combine textures, graphic design, art of many cultures,” she noted in regard to the decor of her house.

Her clothes, though clean-lined, were conceived the same way: They referenced faraway (from New York) cultures and long-ago times. Her work was described as having the quality of “romantic abstraction” by Vogue journalist Jill Robinson in 1977. “I’m not a draping artist. My construction is simple, flat, one-dimensional. I’m interested in limiting bulk, in a total spareness of finishing,” said the designer at the time.

On the most elemental level, however, McFadden’s designs centered around materials. “The effect I’m searching for,” she told The New York Times, “is to have the fabric fall like liquid gold against the body.” In this—and in her use of micro-pleating—McFadden continued the tradition set by Mariano Fortuny and Henriette Negrin, the husband-and-wife team (as the Costume Institute’s “Women Dressing Women” exhibition stressed) who copatented a still-secret way of pleating silk. McFadden’s Delphos-like dresses were made using Marii, a proprietary heat-pleated synthetic fabric that she introduced in 1975.

Vogue credits the designer with transforming the way women dressed for evening in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This was a time of soft dressing, and her longline dresses celebrated the natural body. Though not hippie-ish in the least, they tapped into the prevalent fantasy of other places and other times. Free of constraints, McFadden’s clothes were polished but comfortable, allowing for movement. And women’s lives were changing apace, both in boardrooms and in bedrooms. A McFadden dress was as sensual as it was timeless. As easy-on, easy-off for the evening as Diane von Furstenberg’s wraps were for the day.

She was dubbed a “design archaeologist” by curator Harold Koda. Below, we excavate some fun facts about the designer.

Mary McFadden

1938

Mary McFadden, the daughter of Alexander Broomfield McFadden (a cotton trader) and Mary Josephine Cutting, is born.

1962

McFadden joins Christian Dior New York as director of public relations.

1964

McFadden—described by The New York Times as “a member of the chic young international set”—marries DeBeers executive Philip Harari in a wedding attended by Babe Paley, among others. (Baby Jane Holzer was one of her bridesmaids.) “All the synonyms for pretty fitted the wedding,” noted Vogue. The couple moved to South Africa and set up home near Johannesburg, where McFadden worked for Vogue and wrote for local media.

1968

“Mrs. Harari invites experience. She has no fear and little vanity,” noted the writer of a 1968 Vogue profile. ‘Not only no fear but colossal nerve,’ said a friend. ‘She is the person she is creating. Nothing bothers her. She hasn’t the highest sensibilities, does the most outrageous things, and doesn’t comprehend why you’re shocked. Then you realize you’re shocked because you’re conventional and she’s not. And it doesn’t make her the coziest person in the world; but then, she doesn’t want to be.’”

1969

After divorcing Harari, she marries the director of the National Gallery in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Frank McEwen. They cofound an artisans sculpture workshop, Vukutu, which would fall victim to the political turmoil in the country.

1970

She returns to New York, newly divorced, and becomes a special projects editor at Vogue, where she sometimes wore pieces she had designed for herself and had made in Africa when she lived there.

1972

She’s the subject of yet another glowing Vogue profile, in which the writer enthuses: “In any crowd of her contemporaries, Mary McFadden is an exotic. She blazes her own trails, she thinks and decides for herself. She dresses and decorates in a manner reminiscent of absolutely nobody. In so doing, she is increasingly one of the most fascinating women in New York.”

1973

She starts selling her designs at Henri Bendel and finds success quickly.

1975

She patents Marii, a material from Australia that is dyed in Japan and pleated in the United States. “I started with China silks. I had them hand-painted, quilted, and pleated to give them a distinctive look. I found the pleats really didn’t hold. It took a man-made fabric to get really permanent pleats,” she told The New York Times.

1976

She becomes president of Mary McFadden Inc. and wins her first Coty Award.

1977

Vogue declares that, in three years, McFadden “has practically changed the way women look at night.”

Jill Robinson, who profiled the designer for the magazine, writes: “There isn’t a woman I talk to now who doesn’t respond to Mary McFadden’s name. And I am not just talking to women who follow fashion. My friend Martha Stewart said recently, ‘I saw Mary McFadden shopping. She has these fabulous Vuitton shopping bags and briefcase, and she was all wrapped in a pale gray shawl and carrying everything in the world. She has very long arms and must be terribly strong. It was wonderful to see. She knew exactly what she wanted.’

There is no question, in these past few years, Mary McFadden already has influenced what we wear. She told me, ‘I am going to be a mass designer. On my terms.’ And her terms are selective—her requirement is excellence.

In such places as Newport Beach, California, and Oklahoma City, women are buying and wearing Mary McFadden clothes. From Scottsdale, Arizona, to Birmingham in Michigan and Birmingham in Alabama, women are wearing jewels on satin cords, bindings of silk and braid, doing sashes bandolier style. From New Orleans to Kansas City, they are wearing the coats and the gowns. And in Philadelphia and Memphis (where it all began), lariats of golden leaves drape about bare shoulders, matte bronze grape leaves dangle from slender silk rope.

Women are tying the gold cuffs about their arms with black satin cord, wearing the wheels of gold that make the hands look lean and fragile. In Seattle and Chicago, they are buying McFadden ornaments for the hair, picking up skeins and chignons of artificial hair to add on, as Mary sometimes does at night. And in all of our homes, we are using and seeing art differently. Art melds with craft.”

1979

McFadden is entered into the Coty Award Hall of Fame and receives the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award.

1982

She serves a one-year term as CFDA president. Vogue praises the designer for her “sensuousness, a total sense of sophistication, a modern approach to luxury, and a narrowness of line, a smallness that’s second nature to her whole way of dressing.” Later in the year, the magazine enthuses that McFadden maintained “a terrific sense of line and a very feminine, sensuous approach to dressing.”

1990

She is the subject of a New York magazine cover story, in which she declared: “It’s important to reach for extreme fantasy.”

“Modern Ritual: The Art of Mary McFadden” is on view at Drexel University through October 11.